II

Above the meadow, inside the tree line, the hill slopes steeply to the ridge. From just below the high point knoll there is a ravine bisecting the property down to the bottoms, cleaving it into north and south faces. Deer trails, old logging and mining roads, gas and water line right-of-ways pass above its steepest walls, cut through the brush and old growth. Down in the flat at the end of the ravine, near the creek formed by the wellspring on the south side, is the collection area for the animals I trap. It sits far enough from the house that the smell never reaches the porch in summer, and below the creek so as not to corrupt the water. Some nights I sit with a .25-06 in the shed and spotlight the coyotes that gather around like Thanksgiving family. Those I leave where they lay.

It was on this property that I learned how to walk, fish, ride a bike. Not much later I learned to drive a tractor, then a car. As boys my brothers and I tended the cattle and chickens, cut trees to be sold for support timbers to the mines, plowed the rocky clay until it would yield scrawny corn for feed and trade. I was born here, in this house, along with the past three generations of my family. Sometimes in the waning purple light of evening I’ll think on those older pioneers, squatters in a wilderness not yet described as Appalachia, utterly alone save for each other. I wonder what they had hoped to find here, if this was truly a better life than what they had left behind, whether or not they had a choice. I think about the winter they burned the split rail fence to survive when firewood ran scarce, about the stillbirths, the smallpox, influenza, and farm equipment casualties that populate the family cemetery halfway up the opposite hillside and I wonder if I would have measured strong enough against that standard. There was a time I once carried my older brother Frederick home fireman-style the two miles from our favorite fishing spot. We’d fought after a disagreement involving me popping the eyes off a bluegill with a pen knife. We decided to tell everyone that he had slipped on a rock, breaking his jaw and tearing his ear nearly clean off in the fall. So maybe.

III

On mornings when foodstores are running low I tend to rise early, well before the sun, and hike silently to my favorite hunting spot, a place above the ravine and below the ridge, where the terrain bottlenecks deer as they travel from the grassy fields in which they feed to their thicketed bedding grounds. Taking a spot on the ground below an old oak in the still-dark I’ll watch the woods come alive. First the songbirds cheerfully calling one another, then the squirrels barking and rustling, the distant cluck of a hen turkey. At all times present is the high distant whine of the ventilation-shaft fan at Flat Run, the one that just a few years back in ’68 had quit, filling that mine with gas till it sparked up and blew like the devil himself was coming out of the mountain. Fifty- some-odd men died in it. My maternal grandfather was on the radio with the few of those men who had survived the blast, and who were to be sealed in down there under fly ash concrete to contain the fire, preserve the coal. The fan hasn’t faltered since that. Through binoculars I scan the ridgeline, backlit by the pale sky of first light, looking for any brief, halting movement, the flick of a tail, an ear. A horizontal backline against the cool blue morning. These times allow for quiet reflection, and for the past several days my thoughts have been with a woman.

Her name is Helen, and she is gone from me now.

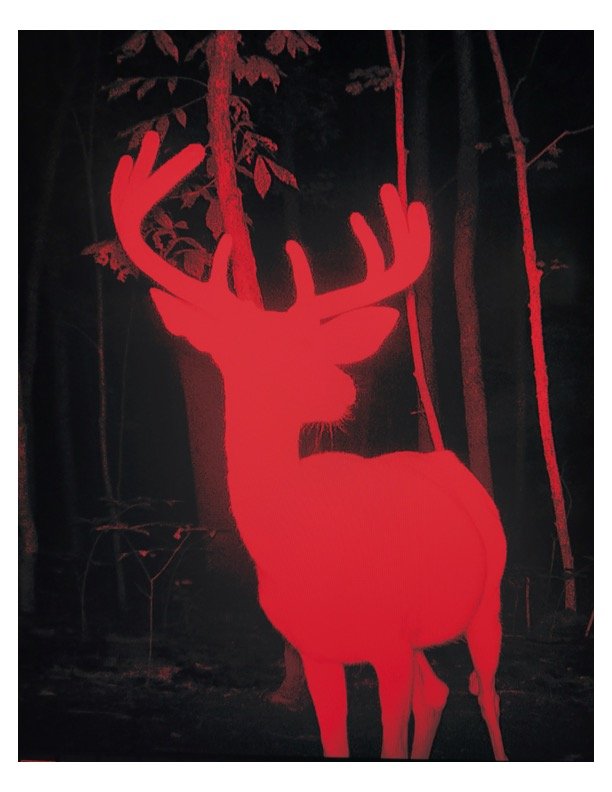

As a child of seven or eight I wounded a deer on one of my very first hunts. It was last light, the sun well below the crest of the hill, and all I could make out was the silhouette of a buck on the ridge a good eighty yards above me, antlers and an elongated neck swollen from the rut. I laid the ironsights on his neck and squeezed the trigger, and when my eyes returned to the spot where he had stood there was only empty sky. My father and I climbed through the saplings and undergrowth to the water line right-of-way, flat and open above the ravine, and found a six-point motionless in the dusk. We decided to field dress the deer down by the house before the pitch dark took us, makes the dragging harder but the deer was small and we had the downhill slope to our advantage. Halfway down, the buck started to thrash and wheeze, trying to regain his feet. I had heard injured deer before, and they can bleat and cry like wounded children when taken in the night by coyotes. But nothing more than barely audible gusts of air came from this one. My father leapt on its back and, producing his skinner from its sheath, beheaded the animal in three short pulls, save a thin band of flesh above the severed spine, grunting loudly with each jagged cut. The stench of blood and animal shit rose with steam from dark pools collecting at our feet.

I had only managed a shot through the neck, knocking the buck unconscious. “Don’t shoot unless you can hit vitals. No need for an animal to suffer like that.” He did not look at me.

“Yessir.”

After dressing and then hanging the deer for a few days we went into the shed to skin and quarter it. On close inspection we saw that its vocal cords had been obliterated by the bullet, its jaw shattered in the upward trajectory. Then we began the slow process of peeling the hide back from the meat, pulling down hard with one hand while teasing free connective tissue with the razor-sharp edge of a knife made for no other purpose.

----

Tune in to Dispatches Every Sunday to Continue Reading “The Kindness of Strangers” by Lou Poster.

Start from the beginning of “The Kindness of Strangers” on SVJ’s Features.

This is Lou’s first published piece.

----

Lou Poster is a Native West Virginian, current resident of the poorest county in Ohio. Appalachian songwriter/singer/storyteller. Son of a third-generation coal miner.