By Ryan Latini

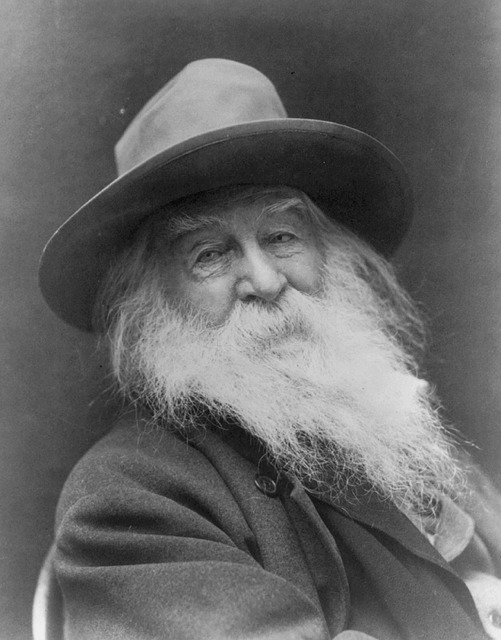

Walt Whitman will be 197 years young on May 31. SVJ will celebrate his birthday month by revisiting Cynthia McGroarty’s 2005 piece “Walt Whitman: Walking in Transcendental Footsteps”.

While I write this intro at my home in Mount Ephraim, NJ, Walt Whitman’s bones lay just 4 miles away in Camden’s Harleigh Cemetery. Whitman spent the last years of his life (from 1884 to his death in 1892) in Camden, NJ. I’ve always felt a nostalgia and a spark of the uncanny when I read Whitman. During college, I worked at a bridge named after him and was born at Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center, which is just a hundred or so yards from his tomb in Harleigh Cemetery.

Whitman was no stranger to similar feelings of kindred spirit and nostalgia of place. Even a city as troubled as Camden has reason to celebrate a man like Whitman. Sure, the city cradles his bones, but can it ever cradle his ideals?

McGroarty’s article takes a look at Whitman’s embrace of transcendentalism ideals; specifically Emersonian thought—the unity of the “common heart”, “Over-soul”, as well as the “celebration of the autonomous individual.” But McGroarty demonstrates that Whitman did not merely borrow thought from popular thinkers of his time; rather, he spun this “celebration” of mankind through free verse, especially in “Song of Myself”, and through a unique take on narrative aspect, he began “positioning his narrator as both individual and encompassing soul: “I am large, I contain multitudes.” For McGroarty, Whitman “administers some metaphoric steroids to the Emersonian vision” and “bursts forth like machine gun fire to hit every possible target” unlike Thoreau at Walden, who had a more individualized, cloistered reflective period.

So if we owe Whitman’s perception to the transcendentalist, to what do we owe the intense heat which still radiates from his words written well over 100 years ago? His revolutionizing free verse? His perspective in narration that was a blend of universal omnipotence and near superhuman empathy, which all the while celebrated the autonomous man?

As McGroarty notes, Whitman embraced the “Emersonian vision of the “transparent eyeball”—the nothing that sees all.” A section of “Song of Myself” that McGroarty focuses on reaffirms not only the overarching perspective and inclusivity that Whitman brought to transcendental thought, but also reaffirms my statement from earlier: that a city as troubled as Camden has something to celebrate in a man like Whitman:

“I see all the menials of the earth, laboring, / I see all the prisoners in the prisons, / I see the defective human bodies of the earth, / […] I see ranks, colors, barbarisms, civilizations, I go among them, I mix / indiscriminately, / And I salute all the inhabitants of the earth.”

It was a paralytic stroke that brought Whitman to spend his remaining years under the care of family and friends in Camden; but it is death that keeps him here as a part of the city, as a monument to American poetry in a city with very few monuments.

In Leave of Grass, Whitman wrote, “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, / If you want me again look for me under you boot-soles.” So, readers, keep looking under your boot-soles for the lost and forgotten. As you celebrate Whitman’s birthday this month, don’t forget to celebrate, as McGroaty notes, “the unity of the “common heart”—or more simply, compassion. As you’ll see in McGroaty’s piece, Whitman had no shortage of compassion.