By Ryan Latini

Happy March from the SVJ archives. In like a lion, out like a lamb—that is the old adage. It holds true for the narrative of Monalisa Greenleaf in Marilyn Brock’s 2011 short story, Saving Mona Lisa, our showcase archival piece for March.

Monalisa is a lioness in the opening paragraphs of the story, but Brock leaves us with a lamb of a woman by the end. The tale is immediate and fast paced, like Monalisa rounding the jogging track—the diligent housewife keeping fit. A staccato is provided by the punctuation in the initial paragraphs. Something is looming. Dissatisfaction?

“The cold is like my husband’s breath, always like he’s been chewing on ice.”

Or is it something more sinister?

“[…] the darkness is too thick to be brush behind those birches and that darkness just keeps…moving.”

You’ll have to read it to find out!

You’ll see that Monalisa is a survivor, but to what end—for what end? Is it worth enduring just to live on in resentment?

“You’d think you’d be happy, having survived […] convalescing in a beautiful home, married to one of life’s winners.”

This short story is worth the read if only for the evolution of what fuels the narrative—the narrative degenerates just as much as its protagonist: fast-paced action gives way to passive observation, which, in turn, devolves into musings and potentials.

We are left musing too: Is Monalisa likable? After all, nothing changes if nothing changes. Pontification, although a verb, is not truly an action.

Here we are, entering the season change. Will Monalisa take the steps necessary to change, or will she keep on rounding the same bends of the jogging track, stuck on the loop, running simultaneously away and toward the selfsame thing?

Saving Mona Lisa

By Marilyn Brock

I’m running. It’s cold out and the air feels hard and unforgiving. Underneath the cold my skin is slick and sticky wet against my sweatpants; my legs break into speed around the last turn—well, maybe one more, if I can. My breathing: it’s getting stronger; fog is freezing in my chest, but my metabolism needs this blast. I’m imagining the pizza melting off my hips: burn, baby, burn. My legs churn faster; I’m on the last lap. Well, maybe one more.

I speed toward the River Birch on my left. The track looks barren, the trees all shorn, the cold having stripped their colors, leaving them dry. I’m happy to run past them, Nikes hard on the soft, red dirt. The track is littered with my footsteps, after years and years of running here. The cold is like my husband’s breath, always like he’s been chewing on ice.

The trees line grand old Cincinnati houses built a hundred years ago. They’ve withstood winter after winter; they stand stoic, wind-whipped, and peeling, filled with families that are never as happy as they aspire to be. I guess I know this, but I don’t know how.

When I was young I wanted to live here, and our house down the street is so close to my dream; only a few blocks from the track, those rich, autumn-glazed birches. But the falls have been growing shorter due to global warming, and though you’d think that means more heat, it’s the winters that have been settling in, barren and unforgiving.

A shadow hovering near the old barn-style house starts to scare me. It’s up fifty feet ahead, just past the bend of the track, a gray-like mass of darkness, slowly, fluidly moving hither. I’m gaining fast on it. There’s no need to worry: the police station is just next door, the air is too cold to invite mean strangers out to stroll…but the darkness is too thick to be brush behind those birches and that darkness just keeps…moving.

I pant my mantra. I will always win. Victory. One more round.

I’m breathing hard, my skin under my bra straps sting. I think, must be the elastic. Tears collect at the corners of my eye. The shadow grows closer, bigger, more shapeless. It moves: like one step out, and I see a head emerging from a hooded shawl. Oh my God, he’s out to hurt me.

Huge, plastic-masked face—male—with shoulders so fierce.

He lunges at me with a switchblade and I can feel it before it hits me because he’s already grabbed me and I can’t move away, but I’m so afraid, there’s no hurt, just fight.

I will win. I’m bleeding, but I believe this anyway. I won’t die. I won’t die. I will live.

Hard shoulders are hurting my hands when I try to hit them, and my knuckles collapse against his black sweater. It’s raining cold, not wet, just cold. I slam my fist harder; my hair is caught in his vicious grip. God, it hurts to have it pulled so much, but I’ll have it ripped all out of my head before I give in.

“Fuck you!” I scream involuntarily, it just happens, and, “Fuck you!” The screams invigorate my body and I’m screaming fuck you and kicking, scratching. My hairs are all over his sweater, but we’re still upright, he hasn’t gotten me to the ground yet. I feel the muscle in my left side compromised and a side-ache from running. Oh, but it hurts much more than that. When I notice it, I get so dizzy. God, this rush of pain is fierce.

And yet I’m cold and the cold makes me stronger.

Fuck you, I will win.

He’s trying to find something, like he is grasping around me, because we are fighting so close, but I can’t tell what or why. I will win. I will win. I will win. I will kick his ass.

And then I fall flat down on my back and he lands hard beside me. Without thinking, I roll sideways and kick his stomach. He screams and after one more useless grasp at my chest, he jumps up and takes off across the parking lot. Now I hear sirens as my perceptual horizon narrows into a fuzzy little hole, like I’m alive but the world around me is half asleep.

As the sirens near, I turn my frozen head and faintly see the outline of a little boy in a nearby yard. He’s at the barn-house. Lives there, I believe. With his big, black dog, they’ve watched me run daily. The house that is never happy. It is not my house. Grant and I, we do not have children. And then the hole closes.

In my coma I had memories of date night in our patio Jacuzzi. Carmilla and Tim were there, just walked over from next door in bathing suits, Carmilla carrying the champagne, Tim the cigarettes, and we were soon all in the spa. Foam filled the center of the tub, detergent from our bathing suits, I was thinking, feeling beautiful in the humid summer air while resting against flowing water jets. Carmilla ruined her cigarette while sucking on it, and laughed, so drunk. “It broke. My lips are wet,” she said.

“Would you like another?” Grant asked, climbing out of the tub, and scratching my leg in the process by accident. So ironic—my husband, the obstetrician, fetching cigarettes for the neighborhood swinger; I thought of his anti-smoking posters and our kissing pre-marriage.

“Yes, take it away.” Carmilla flung her free hand, lightly splashing me. Tim’s hand rubbed up my leg. I tried to enjoy the feeling, but I could only concentrate on hating Grant. Who invited them here?

It was miserable, waking up in the hospital; my limbs felt loose and gummy and numb. The pain in my side was the focus of my consciousness for the first few days, even beyond the inevitable deliberations about the identity of my attacker—the pain was so pure and striking, like a muscle ripped clean in two. I spent much of my recovery alone and finally had to stop wondering who had attacked me, because it was impossible to figure out and only painful to imagine. I was in a thin cotton gown and wrapped in gauze about the waist. My head ached though a pillow was soft beneath my neck; Grant had put it there. My sight was marred by a faint black speck in my right eye, and I had the sense that I was in another person’s body. I remembered everything about what had happened, and told the police as much as I could: the dark mask, the big shoulders, a glinty knife, the barn-house, and the little boy who saw.

Back home, wrapped in a soft, pink acrylic blanket that smelled like Downy, I watched TV a lot. Quickly I discovered I was a little news sensation. Not too many joggers attacked in Cincinnati, not in our neighborhood, not on our birch-lined running track, not on our snowy, winter streets. One bit I saw on myself, on channel nine, showed this awful picture: I looked at least ten pounds overweight. I couldn’t imagine how they’d settled on that one. I tried to call for Grant, picturing him sitting in our colonial living room, amid all the blues and golds and tans, or his nautical office — he was always at work — to see if he knew how they’d gotten a hold of that picture, which I thought was from a Rotary meeting three years ago, and the blue shift I was in, was just one step from a muumuu. Grant did not answer; he was out of earshot. I could hear his sports radio playing in the next room, then the phone ringing. He’d be off to deliver. All the crying babies he must hear.

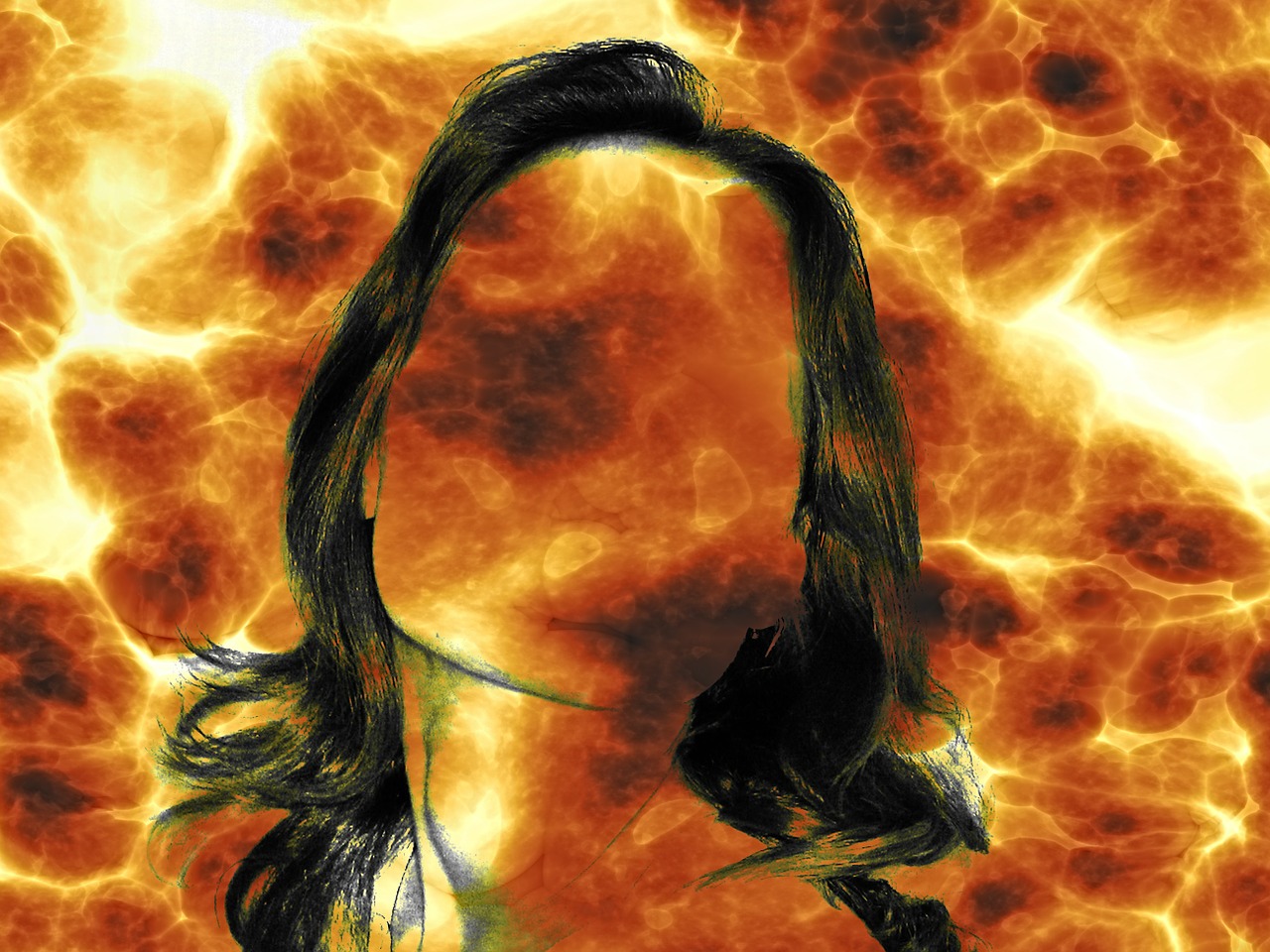

Funny what comes to mind when you are unable to leave your house, watching naked trees through the windows, from inside your warm cocoon. I used to think that love conquered all. I had boyfriends that I once loved, before marriage, relationships that for a time put me into that “Nothing can harm me” phase, like I was securely padded in some emotional layer of protection from the world. Leonardo was my lover in Florence, when I lived abroad for a semester, and I spent most of my afternoons learning Italian, firsthand, in the basement of a villa half-covered in grapevines. I never thought to dream that spring; the present was full enough to blanket any thoughts of the future or past. Now, in recovery, I found it hard to invest those memories with any sense of the real. You’d think you’d be happy, having survived someone trying to kill you, convalescing in a beautiful home, married to one of life’s winners. You have media coverage of your philanthropy; you have sympathy flowers swelling up in your hall- ways, steeped in deep vases, covering your dressers, scenting all your rooms. Yet the heater was too strong, and the pink blanket needed to be washed after so many days in the bed, as did my hair, which had definite bald spots I had not even touched. And I was alone and could not run. Believe it or not, I still wanted to run, and the pain in my side was incisive.

And Grant was as busy as ever, his radio going in the other room, outside or at work, taking care of me but hardly speaking. There’s a strange caged loneliness to marriage, when you are tied to someone who doesn’t love you, yet whom you live for. If you have children, you can flounder in their dependence, drowning your needs in the martyrdom of motherhood, complain of too much work to do, too many diapers to change, too many dishes to wash, complain of a bad paint job on the living room walls, your husband’s inconsideration.

But without the distractions, there is only you, the chatter in your head, and your husband’s inconsideration. The loneliness is a glaring bulb without a lampshade, illuminating the bad paint job on your living room walls. Then there are only the walls. And the paint is everything. Fresh, ugly paint.

Funny that when he first got through medical school, and his success was my self-esteem, I used to sleep with the radio in my arms when he spent nights at the hospital. I used to fall asleep to the running sports commentary, dreaming about touchdowns and home runs. I used to dream about our sons being track stars, our daughters being princesses. I thought we had the money, the neighborhood, the house. I thought the children down the block were auguries of our own. I’d keep in shape, our house would stay painted, and our love and money would be enough.

But there’s something transient about attachment that can slip away into darkness, a moving darkness that haunts, and attacks out of nowhere. My shadow self, the one blocked by the identity I keep with Grant, keeps gnawing and kicking at an inner drive to fear it and to fight it because I want to stay Monalisa Greenleaf, who I used to love being. She is the only self I can trust will survive. Becoming this new thing—a jealous plague, a scratched-out oil painting filled in with sketch…there’s so much misery to spread with your emptied-out self. I smoothed my hair with dry hands and knew I was becoming someone else; that Mrs. Greenleaf was already far removed, maybe for years already, lost somewhere in Italy, slumbering on a warm evening.