PHOTOGRAPHING THE WORKSHOP OF THE WORLD

“…a way of remembering what it would impoverish us to forget.”—Robert Frost

By David Livewell

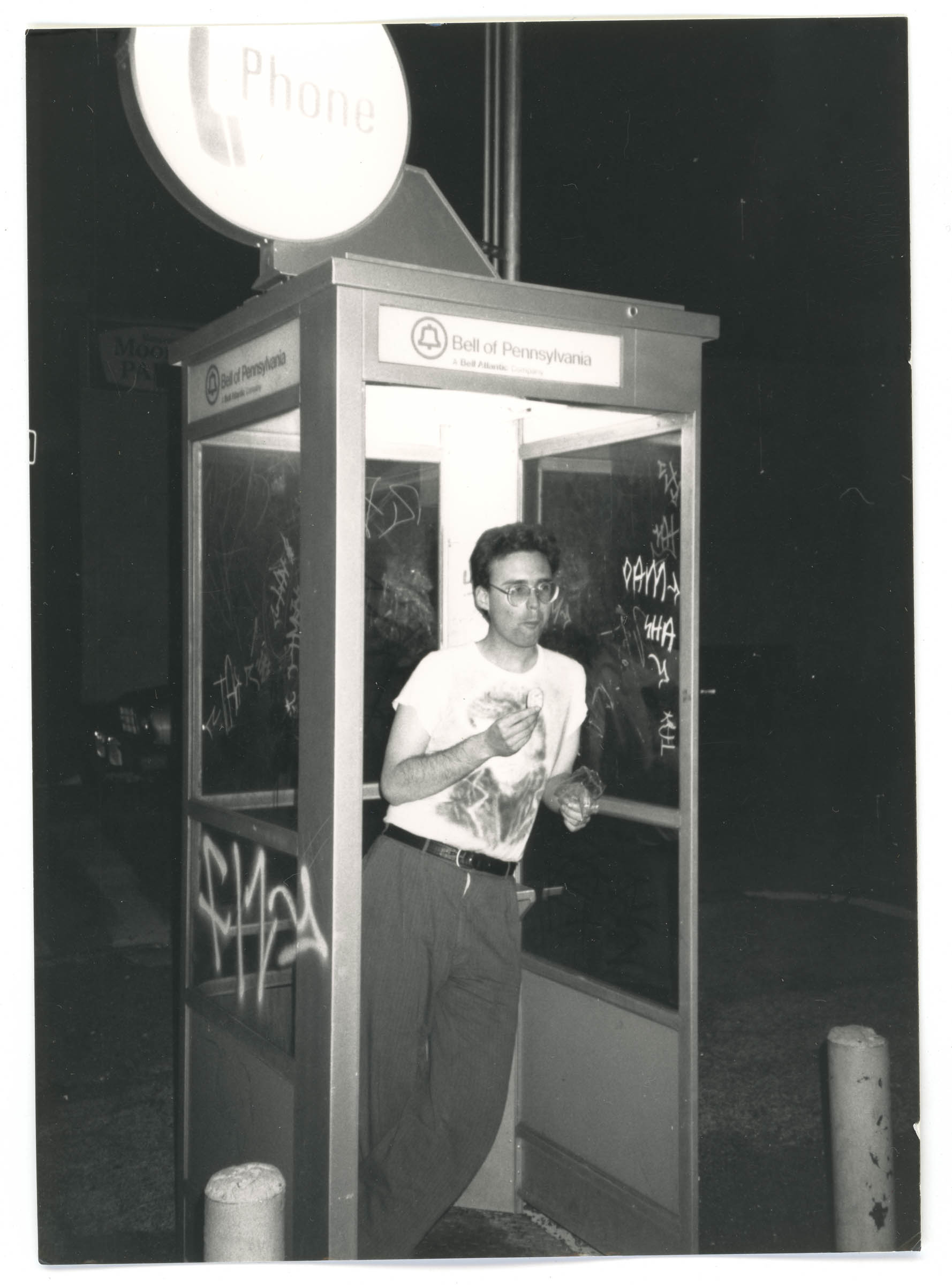

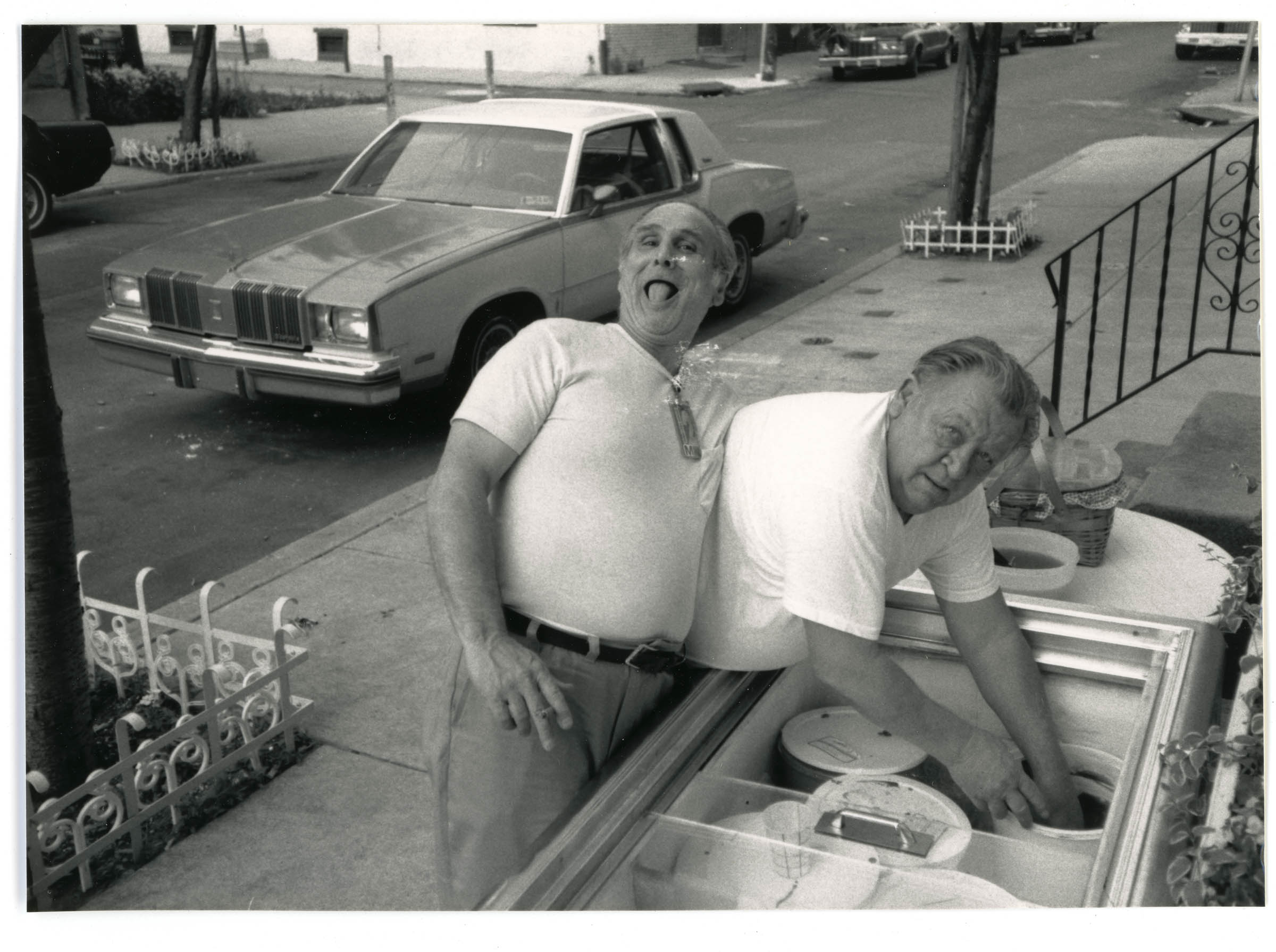

Neighborhoods are unique in this city, and memories about neighborhoods are unique to each resident. Residents shaped the streets of Kensington, and the streets shaped the residents. Of course the place was an easy target in the 1970s and 1980s. Outsiders could concentrate on the obvious negatives—crime, unemployment, racism, poverty, and graffiti. But how can outsiders know the surprising strength and humor of those who lived there? How can outsiders know the strange and unique beauty of vacant buildings and empty lots and the history they contained?

The Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, located in South Kensington, has launched a year-long collaboration that provides a photographic narrative of South Kensington, my old neighborhood. I was privileged to participate in this project, offering a few hundred family photos and photos I took in the neighborhood as a teenager.

As I grew up, I was reminded that every former generation in Kensington had it harder than we did. The elders experienced hardships from wars and the Great Depression. By the time I arrived, urban plight was the feared monster. Decay mixed with poverty. Kensington was a true American melting pot. The families who stayed could not afford to flee to the Northeast or the suburbs.

These photographs froze moments: one place, one day, one moment. The place told stories, but I didn’t really see my neighborhood until I was in my late teens. I looked at it, but I didn’t really see it for what it was. For one thing, it was decaying and fading before my eyes. This area was left to rot slowly by the city. We had the worst trash pick-up, the deepest potholes, delayed snow removal, and some of the lowest taxes. I heard recently that Philly was ranked as one of the angriest cities in America. If you grew up in Kensington, you can understand why.

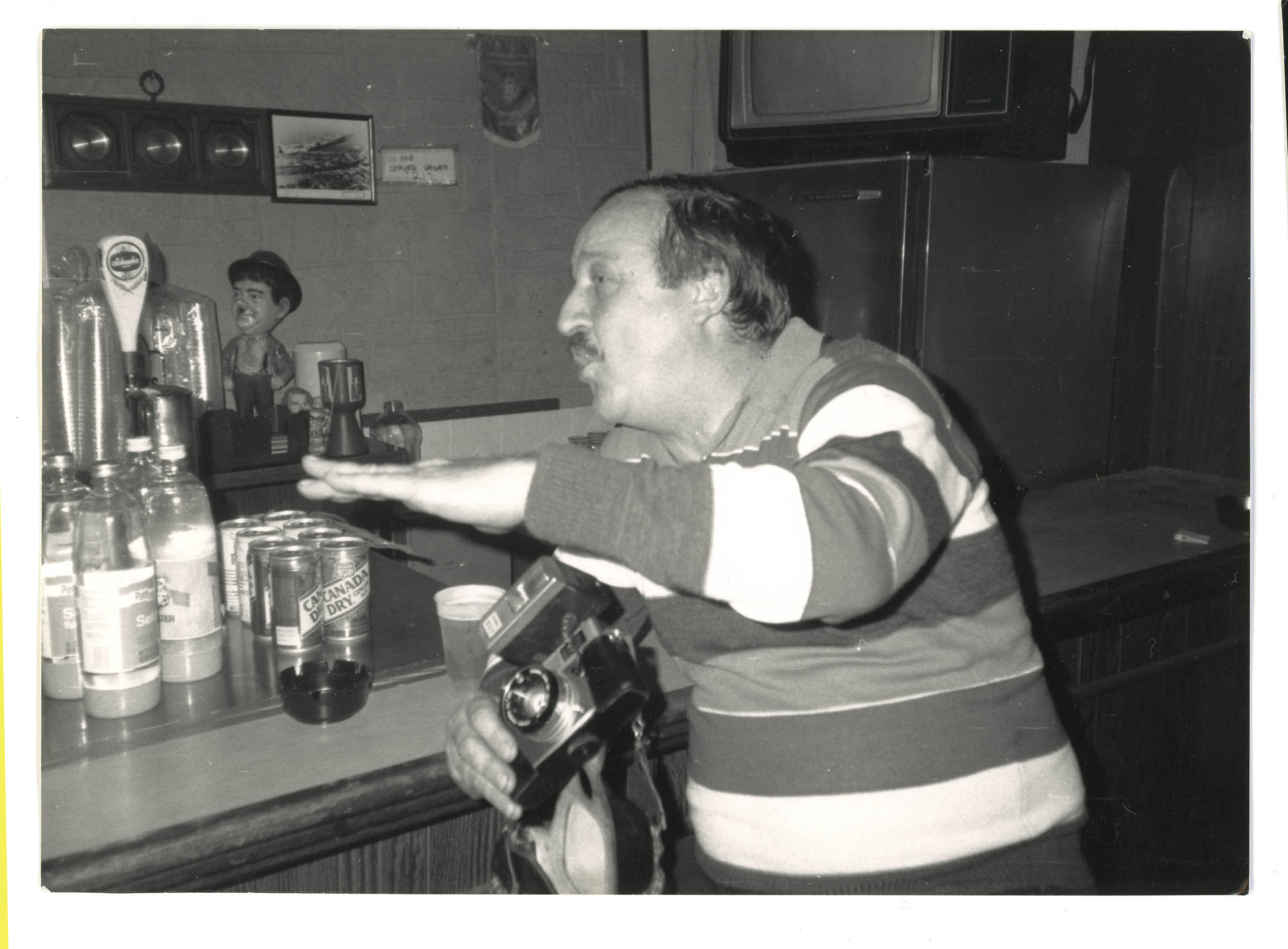

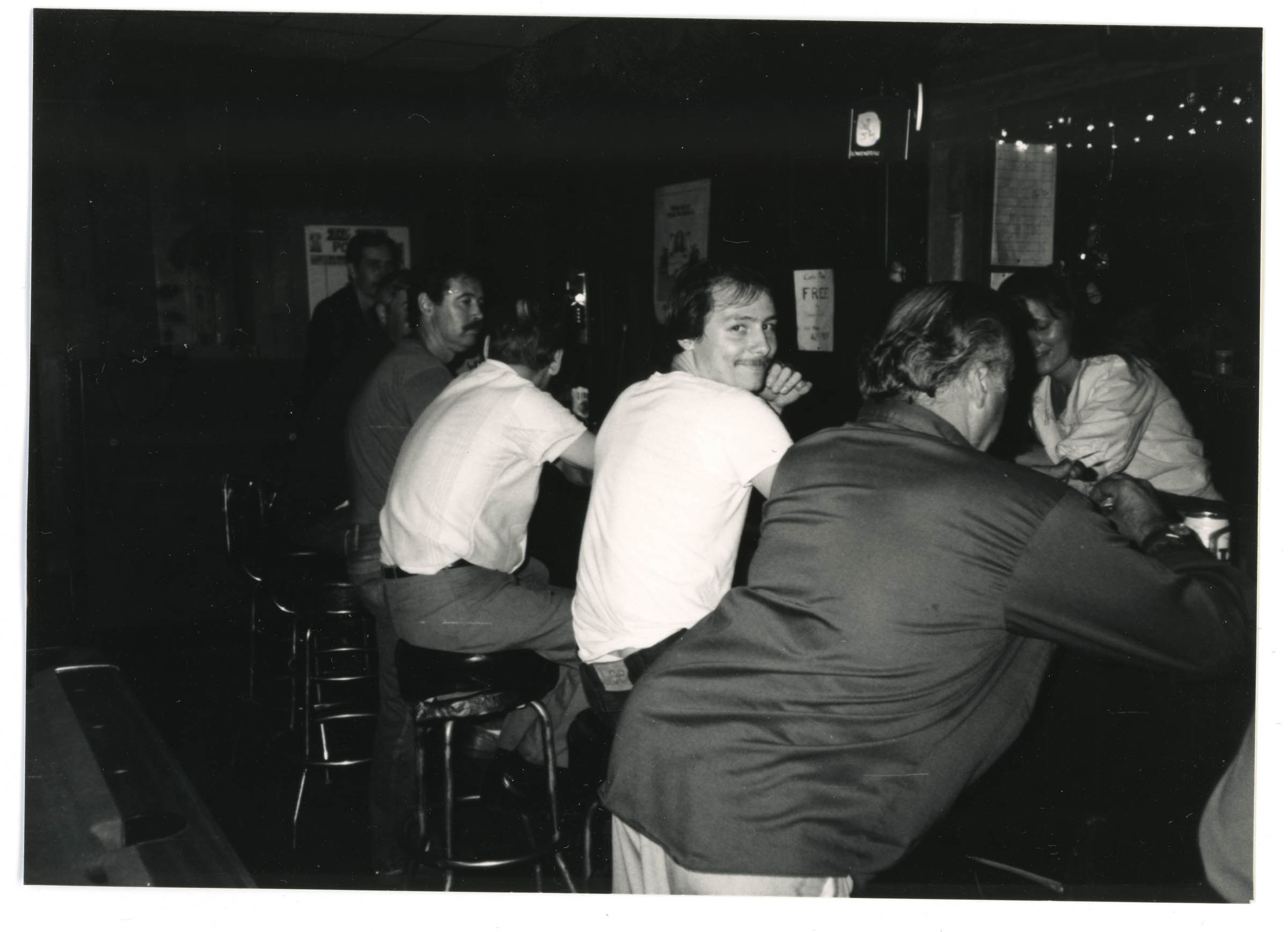

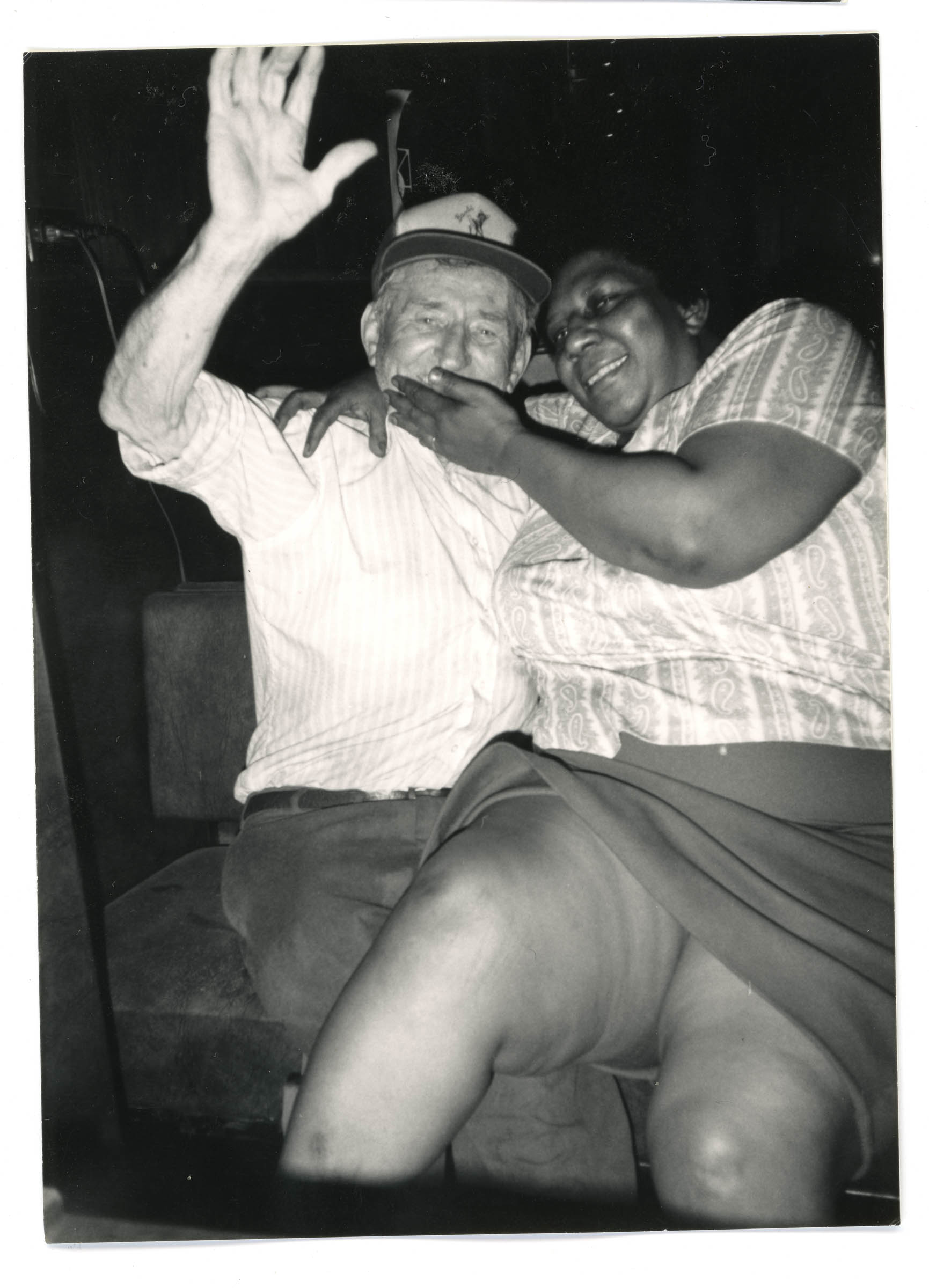

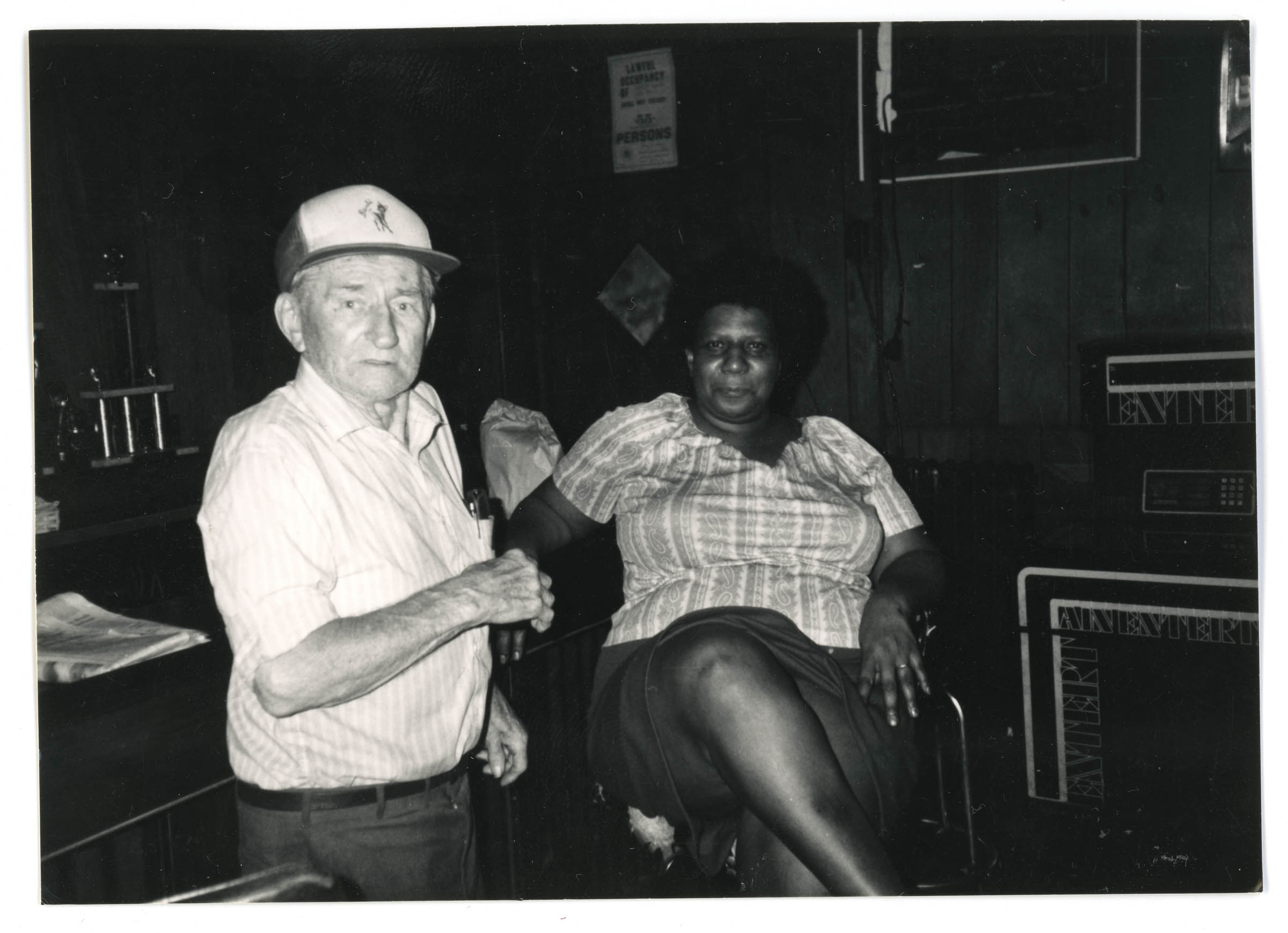

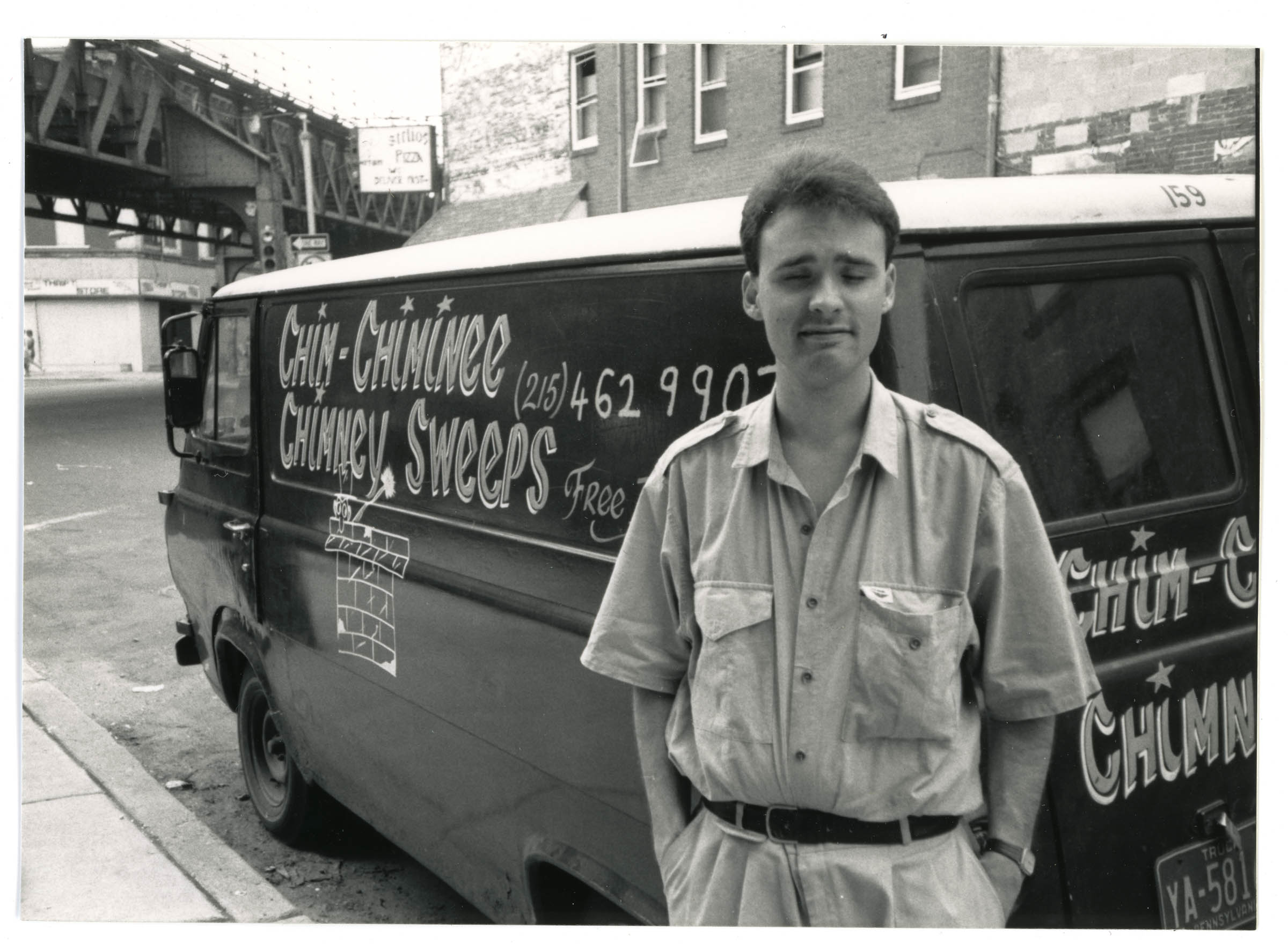

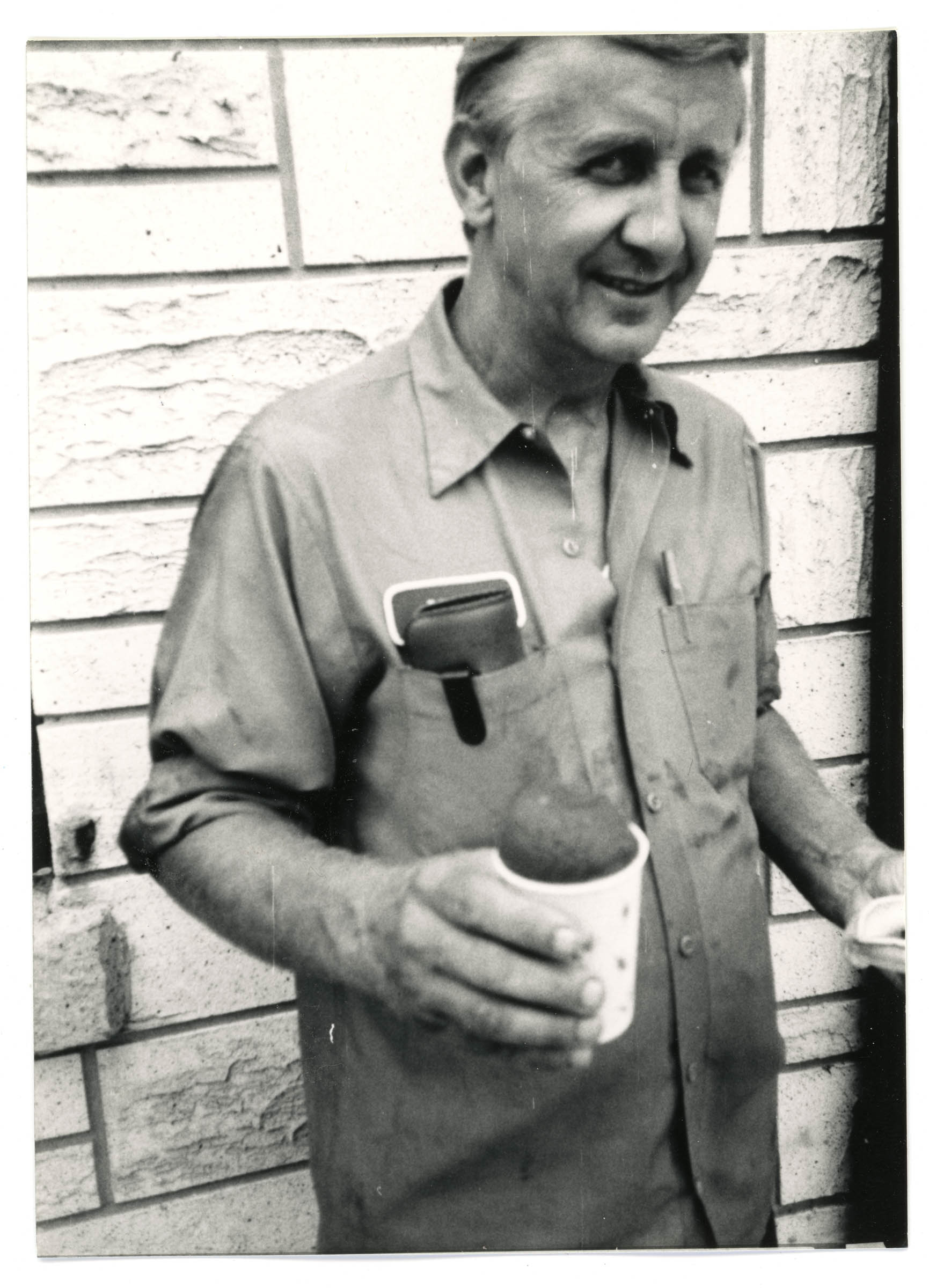

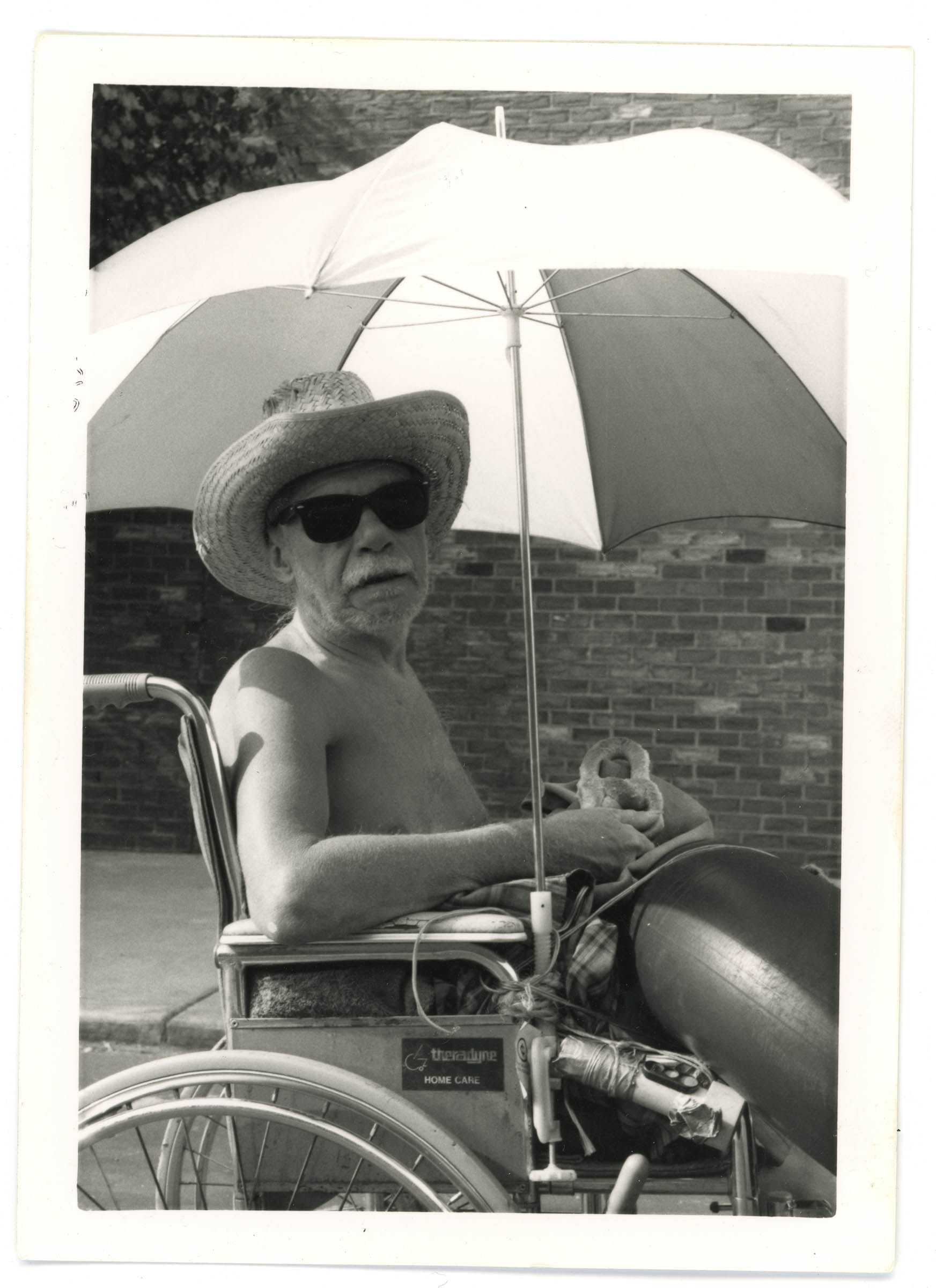

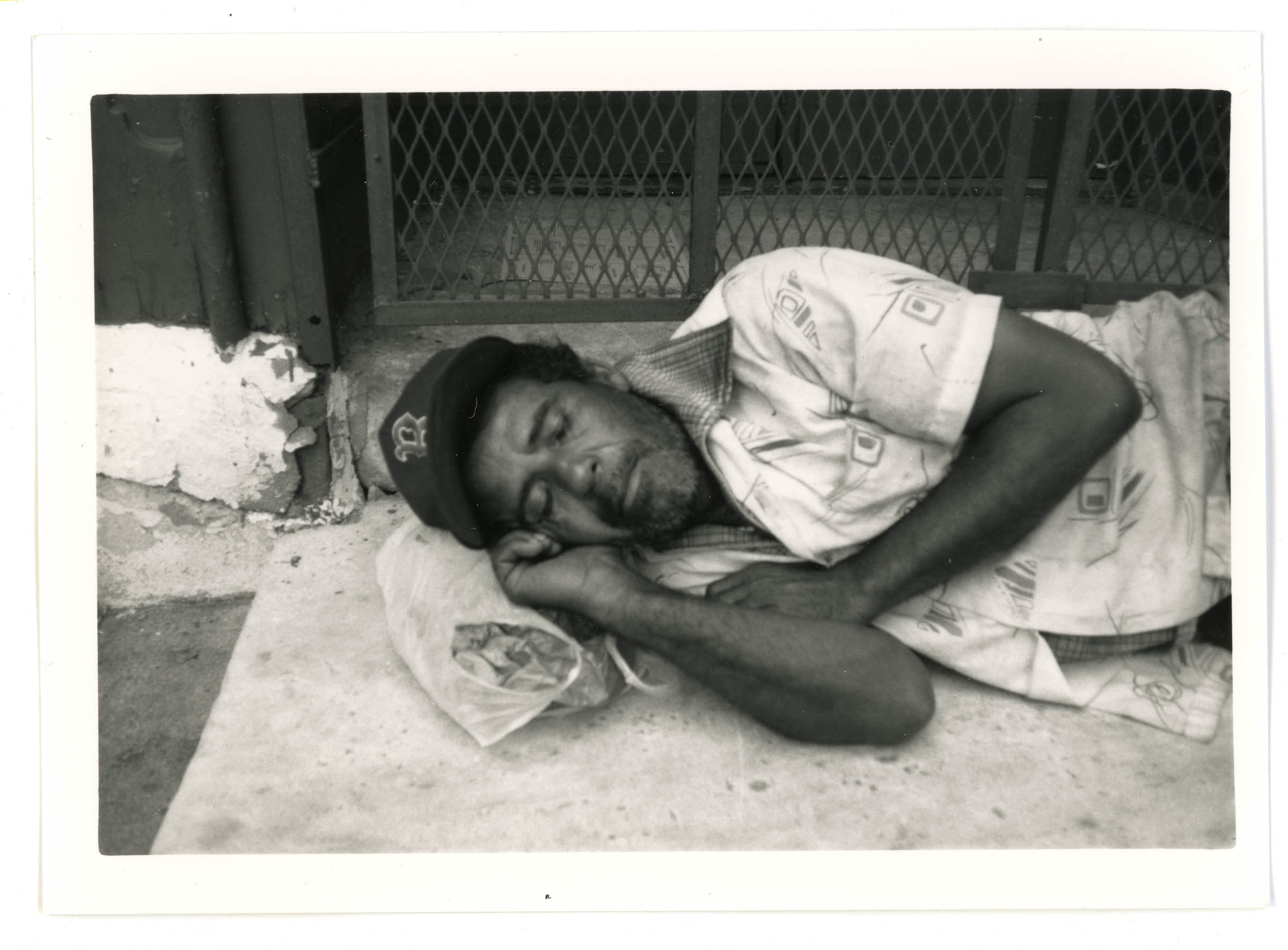

Yeats said that “Things reveal themselves passing away.” My grandfather, who lived next door to us, taught me that truism as well until his passing at 97. He allowed me to take tours through his own century of memories. He was born in Kensington in 1905. Many of his photos are in this exhibit as well. He can be seen with friends and his new bride in the 1920s on these very streets. The houses and windows still looked colonial. Ben Franklin could have recognized the vicinity. Grandpop remembered Kensington when it was called “The Workshop of the World” because of its many mills and factories. Through his remembrances, I learned that words and photos held history in a unique way. I liked the integrity of the single human voice and the single, individual vision of the camera lens. By my teen years, I connected the architecture, the history, and the stories. Everything around me deserved my attention. The narrative of these streets couldn’t be told fully by journalists or historians. Art could redeem the past, compress it, and use it for something new, telling untold stories for the first time. Photography, basketball, music, and writing became my main areas of expression and creativity, my centering points. The working poor in my neighborhood needed beauty and expression as much as anyone. Neighbors knew that I was armed with a camera every day. They started to suggest photos, pose for photos, and take me to people and places that might hold interest for me. I shot the inside and outside of old mills, cobbled industrial streets near the river, burned-out piers, graveyards, coal yards, and vacant churches. I took portraits of anyone who would allow it: vendors, store owners, the homeless, local workers, and neighbors of all ages. In the photos, these people I stood beside in the 1980s still look as if they are about to speak and move at any moment—and yet I will never hear or see most of them again.

One of the most remarkable things about this section of the city was that we were racially integrated before a lot of other neighborhoods. After race riots and territorial gangs had failed, my generation had to get along, the ultimate example of the immigrant experience.

Photography helped too. I could contemplate a scene or a person later without gawking at the subject in the moment. My photographs were like traces of people, like footprints where they once walked. People live inside their memories. We have no language for pure emotion, but a snapshot can capture a mood. I could catch little details I wouldn’t see in life. I knew I wanted to write someday, and that my writing would contain the neighborhood. I didn’t know if that meant fiction, poetry, or memoir. Although I wasn’t a skilled photographer and didn’t know the technical aspects of a camera, I wanted to capture and document what I saw. I knew that I was witnessing a unique history much larger than my vantage point. The colonial past and Victorian past were always there, just below the surface.

Oliver Wendell Holmes called photographs “mirrors with a memory.” As I look at this exhibit, I see the past in each momentary narrative. I see my own past there in a clearer light. I know the architecture and the emotions on the people’s faces. I can sense the weather. I can smell the seasons mixing with the fumes from the factories and the unmistakable scent of the Delaware River.

Art can do what life cannot: it can slow down the march of time. The mind can go back to a moment over and over again with the advantage of hindsight, experience, and imagination. A tapestry emerges. Unlike things can join. Metaphors can be discovered.

Photographs and poems allow that kind of discovery— when the private temperament meets with the public and when the present meets with memories of the past. Art should do more than preserve or document life. It is not a diary. Art should discover something new and transform the maker and the audience. Mostly, we are powerless as we go through life, but we do have the power to transform how we remember our past. We can’t live in the past, but the past can live in us. If the past slips away and becomes invisible, the imagination dies.

The past of Kensington is now visible to all in a gallery on American Street that was once a factory in the “Workshop of the World.”

A Note About the Author: David Livewell grew up in Kensington and won the 2012 T.S. Eliot Poetry Prize for his book, Shackamaxon (Truman State University Press).